Patterns and Personality Correlates of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Christians and Muslims

|

|

|

- George Fitzgerald

- 8 years ago

- Views:

Transcription

1 Patterns and Personality Correlates of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Christians and Muslims WADE C. ROWATT LEWIS M. FRANKLIN MARLA COTTON We explored implicit and explicit attitudes toward Muslims and Christians within a predominantly Christian sample in the United States. Implicit attitudes were assessed with the Implicit Association Test (IAT), a computer program that recorded reaction times as participants categorized names (of Christians and Muslims) and adjectives (pleasant or unpleasant). Participants also completed self-report measures of attitudes toward Christians and Muslims, and some personality constructs known to correlate with ethnocentrism (i.e., right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, impression management, religious fundamentalism, intrinsic-extrinsic-quest religious orientations). Consistent with social identity theory, participants self-reported attitudes toward Christians were more positive than their self-reported attitudes toward Muslims. Participants also displayed moderate implicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims. This IAT effect could also be interpreted as implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians. A slight positive correlation between implicit and explicit attitudes was found. As self-reported anti-arab racism, social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, and religious fundamentalism increased, self-reported attitudes toward Muslims became more negative. The same personality variables were associated with more positive attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims on the self-report level, but not the implicit level. INTRODUCTION According to social identity theory (Hogg 2003; Tajfel 1982), identification with a social group often produces noticeable in-group/out-group biases (e.g., more favorable evaluations of one s in-group relative to an out-group and less favorable evaluations of an out-group relative to an in-group). In this study, we assessed implicit and explicit evaluations of two religious groups, Christian and Muslim, within a predominantly Christian sample in the United States. We also examined whether some religious and social-personality constructs known to correlate with ethnocentrism and prejudice such as social dominance, right-wing authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, Christian orthodoxy, religious motivations, and social desirability correlate with implicit and explicit measures of attitudes toward Christians and Muslims. A better understanding of the social-personality correlates of these attitudes might help partially explain the extensive range of peaceful and turbulent Christian-Muslim encounters throughout history (see Goddard 2000) and could contribute to the improvement of some future Christian-Muslim relations. SOME PROBABLE INFLUENCES ON CHRISTIANS ATTITUDES TOWARD MUSLIMS Although beyond the scope of this investigation, it is important to acknowledge that other dynamics beyond personality (e.g., social, political, economic, etc.) influence Christian-Muslim Wade C. Rowatt is Associate Professor in Psychology and Neuroscience at Baylor University, One Bear Place #97334, Waco, TX Wade Rowatt@Baylor.edu Lewis Franklin is a candidate for the Master of Divinity Degree at George W. Truett Theological Seminary, Baylor University. lewis@franklin.org Marla Cotton was an undergraduate psychology major at Baylor University. marla cotton@yahoo.com Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (2005) 44(1):29 43

2 30 JOURNAL FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGION attitudes and encounters (Goddard 2000). A history of positive social encounters with a Muslim in one s community, for example, could lead to a general positive evaluation of Muslims as a group (Goddard 2000). Consumption of moderate anti-muslim bias in the U.S. news media over time (Madani 2000), on the other hand, could contribute to the development of ethnic prejudices (see also Martin, Grande, and Crabb 2004). It is also important to acknowledge that several factors likely operate at different levels of the person and situation across time to influence attitude formation (e.g., biological, psychological, personality, social, cultural; see Eagly and Chaiken 1993). Possible person-by-situation statistical interactions would further complicate the prediction of these attitudes. Instead of trying to identify and measure each potential influence on attitudes toward Christians or Muslims at these different levels of analysis across time, we opted for a more narrow empirical approach. That is, after reviewing the existing literature to identify some known personality constructs and religious dimensions that correlated with ethnic prejudices, we used those variables as predictors of explicit and implicit attitudes toward Christians and Muslims at one point in time. DEFINING IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES Before reviewing some personality correlates of prejudice, it is necessary to differentiate between two levels of psychological attitudes. Explicit attitudes are expressed evaluative reactions that operate on a more conscious level and are traditionally measured with multi-item self-report scales (Himmelfarb 1993). Implicit attitudes, in contrast, are relatively automatic evaluations that are assumed to operate largely outside of conscious awareness (see Banaji, Lemm, and Carpenter 2001). Implicit attitudes can be inferred from reaction times to make implicit associations (see Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz 1998), from reaction times to categorize items after certain evaluative primes (see Wittenbrink, Judd, and Park 1997), from unobtrusive behavioral measures (see Crosby, Bromley, and Saxe 1980; Franco and Maass 1999), and in other ways (see Fazio and Olson 2003). As the following review indicates, very little research exists on personality and religious correlates of implicit attitudes toward social groups. SOME KNOWN PERSONALITY-LEVEL PREDICTORS OF PREJUDICE Some of the most frequently studied personality-level correlates of ethnocentrism and prejudice include religious orientations (intrinsic, extrinsic, quest; see Batson et al. 2001; Batson, Schoenrade, and Ventis 1993; Donahue 1985; Herek 1987), noncreedal religious fundamentalism and right-wing authoritarianism (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992; Hunsberger 1995, 1996; Laythe et al. 2002; Laythe and Kirkpatrick 2001; Rowatt and Franklin 2004), Christian orthodoxy (Hunsberger 1989; Kirkpatrick 1993; Laythe et al. 2002; Rowatt and Franklin 2004), and social dominance orientation (Heaven and St. Quintin 2003; Pratto et al. 1994). Intrinsic religious orientation religious activity as an end in and of itself usually correlates negatively with self-reported ethnic prejudice; whereas, extrinsic religious orientation religious activity as a means to other personal or social ends usually correlates positively with self-reported ethnic prejudice (see Batson, Schoenrade, and Ventis 1993; Donahue 1985). Quest orientation usually correlates negatively with overt and covert measures of prejudice (Batson, Schoenrade, and Ventis 1993). When racial prejudice was measured indirectly as the discrepancy between preference to be interviewed by a white or black interviewer, intrinsic religious orientation was not significantly correlated with racial prejudice (Batson, Naifeh, and Pate 1978). An experiment in which a more indirect measure of prejudice was used choosing to sit by a black or white person revealed similar patterns (Batson et al. 1986). As such, the intrinsic component of religiosity could be more directly related to the need to appear unprejudiced than to being unprejudiced.

3 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS 31 Noncreedal religious fundamentalism usually correlates positively with self-reported prejudices (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992; Laythe et al. 2002; Wylie and Forest 1992). However, religious fundamentalism correlates strongly with right-wing authoritarianism and Christian orthodoxy,so some of the variation in prejudice attributed to religious fundamentalism could be due to authoritarianism or orthodox beliefs. For example, in a recent study in which self-reported religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism, and Christian orthodoxy were intercorrelated (rs > 0.50), religious fundamentalism did not account for unique variation in implicit racial prejudice (Rowatt and Franklin 2004). However, right-wing authoritarianism was positively correlated with implicit racial prejudice, and Christian orthodoxy was negatively correlated with implicit racial prejudice when religious fundamentalism and social desirability were simultaneously controlled (Rowatt and Franklin 2004). Laythe et al. (2002) documented a very similar pattern when predicting self-reported racial prejudice. Previous research also confirms that religious fundamentalism and right-wing authoritarianism are consistent correlates of negative attitudes toward women and homosexuals (Hunsberger 1996; Hunsberger, Owusu, and Duck 1999; Rowatt et al. 2004). Social dominance orientation (SDO) is another construct that accounts for variation in a variety of social attitudes and prejudices, but has not been administered in many studies of religion and prejudice. By definition, people who score high on SDO desire one s in-group to dominate and be superior to out-groups (Pratto et al. 1994). SDO correlates negatively with pro-social dimensions of personality (e.g., concern for others, communality, tolerance, altruism), negatively with attitudes toward a variety of policies (e.g., social programs, racial, women s rights, gay and lesbian rights, environmental programs), positively with several conservative ideologies (e.g., antiblack racism, nationalism, sexism, patriotism, cultural elitism, political-economic conservatism), and minimally with Protestant work ethic (Pratto et al. 1994). SDO correlates positively with anti- Asian and anti-aboriginal attitudes (Heaven and St. Quintin 2003), as well as anti-arab racism and attitudes toward the 1991 Iraq War (Pratto et al. 1994). Pratto and Shih (2000) examined whether persons with high and low SDO make different implicit in-group/out-group evaluations. High-SDO persons displayed implicit group prejudice only when in-group context was salient (i.e., displayed faster evaluation times to decide if a word was bad when out-group was primed than when in-group was primed and displayed slower evaluation times to decide if a word was good when out-group was primed than when in-group was primed); however, when social context was not made salient, high- and low-sdo persons did not differ in evaluation time to categorize good and bad adjectives when primed with an in-group word (i.e., our) or out-group word (i.e., them). Consistent with Pratto s research, we expect to find that SDO correlates with self-reported prejudice, but not implicit prejudice (because social context will not be made salient in this study). Although sometimes overlooked, socially desirable responding is an important variable to take into account when studying potentially sensitive self-report evaluations. Self-presentational concerns could lead a person to report more positive attitudes or personality qualities than are truly held. We statistically controlled for socially desirable responding in some analyses. We also selected a measure of implicit attitudes (the Implicit Association Test; IAT) that is particularly resistant to faking (see Banse, Seise, and Zerbes 2001) and used the conventional IAT scoring method to omit out-of-range responders (see Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz 1998). THE IMPLICIT ASSOCIATION TEST Several researchers have developed IATs to study implicit evaluations of the self relative to various groups (Cunningham, Nezlek, and Banaji 2004; Devos and Banaji 2003; Nosek, Banaji, and Greenwald 2002). In general, IATs assess the strength of associations between concepts by timing how long it takes a person to sort pleasant and unpleasant words along with symbols that

4 32 JOURNAL FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGION represent two distinct groups (e.g., flower-insect, in-group/out-group; see Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz 1998; Greenwald et al. 2002; Greenwald and Nosek 2001). In the critical trials, categories into which people sort words are combined to be more congruent (e.g., in-group+pleasant; out-group+unpleasant) or incongruent (e.g., in-group+unpleasant; out-group+pleasant) with ingroup participants existing attitudes. An important underlying assumption of the IAT is that more closely related concepts and attributes (e.g., in-group and good; out-group and bad) are more quickly processed than less related concepts and attributes (e.g., in-group and bad; outgroup and good). In other words, the faster a person correctly sorts words into a combined category, the stronger the implicit association between concepts. An implicit prejudice exists when a person more quickly associates the out-group with unpleasant terms than with pleasant terms (relative to the in-group). With regard to implicit associations based on ethnicity, for example, most white people take significantly longer to sort words and faces into incongruent categories for them (e.g., white+unpleasant; black+pleasant) than into congruent categories for them (e.g., white+pleasant; black+unpleasant), a reliable pattern referred to as the race IAT effect (Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz 1998). We selected the IAT to measure implicit attitudes toward Muslims relative to Christians because IATs are internally consistent (Banse, Seise, and Zerbes 2001), temporally reliable (Cunningham, Preacher, and Banaji 2001), valid (Devine 2001; Dovidio, Kawakami, and Beach 2001; Gawronski 2002; Greenwald and Nosek 2001; Nosek, Greenwald, and Banaji 2004), and correlated with some relevant behaviors (see Fazio and Olson 2003). For example, implicit shyness (measure with an IAT) uniquely predicted spontaneous shy behavior (Asendorpf, Banse, and Mücke 2002). Increases in white college students implicit racial prejudice (measured with an IAT) were associated with more negative behavioral interactions with a black research assistant than with a white research assistant (e.g., less speaking time, less smiling, more speech errors, more speech hesitation; McConnell and Leibold 2001). IMPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD SPECIFIC RELIGIOUS GROUPS In one of the first studies of implicit attitudes between members of religious groups, Rudman et al. (1999) found reliable evidence of implicit intergroup prejudice based on Christian and Jewish religious ethnicity. Christian persons more quickly sorted names (of Christian and Jewish persons) and adjectives (unpleasant or pleasant) when the sorting categories were congruent for them (Christian+pleasant; Jewish+unpleasant) than when the sorting categories were incongruent for them (Christian+unpleasant; Jewish+pleasant). Jewish persons more quickly sorted names and adjectives when the sorting categories were congruent for them (Jewish+pleasant; Christian+unpleasant) than when the sorting categories were incongruent for them (Jewish+unpleasant; Christian+pleasant). More recently it was found that college students who watched more media coverage of the military conflict with Iraq displayed more implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians (Martin, Grande, and Crabb 2004). OVERVIEW AND PREDICTED PATTERNS The primary purposes of this study were to assess implicit and explicit attitudes toward Christians and Muslims and to examine whether known personality correlates of ethnocentrism and prejudice (e.g., authoritarianism, SDO, religious fundamentalism) account for variation in these attitudes. Toward these ends, we developed a Christian-Muslim IAT and administered it along with self-report measures of attitudes toward Christians and Muslims and some other social-personality constructs known to correlate with ethnocentrism. Given most humans tendencies to identify with an in-group, to favorably evaluate in-group members, and to denigrate out-group members (Hogg 2003; Tajfel 1982), we expected participants in this sample (comprised mostly of Christians) to express positive attitudes toward

5 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS 33 Christians and neutral or slightly negative attitudes toward Muslims. We expected Christian persons to have slight to moderate implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians (i.e., increased response latencies when sorting words into categories that are more incongruent Muslim+pleasant; Christian+unpleasant than when sorting words into categories that are more congruent Muslim+unpleasant; Christian+pleasant). This pattern, if present, will also be interpreted as implicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims. We expected self-report measures of religiosity (e.g., intrinsic, religious fundamentalism, Christian orthodoxy), right-wing authoritarianism, and social dominance to correlate negatively with self-reported attitudes toward Muslims and with preference for Christians relative to Muslims. Because many non-muslim Americans associate being Muslim with being Arab (Slade 1981), we predict that anti-arab racism will correlate negatively with self-reported positive attitudes toward Muslims. METHOD Participants The initial sample comprised students (138 women; 28 men; M age = yrs., SD = 2.60) at a private university in the southwestern United States who participated in exchange for extra credit in a psychology course during the Fall 2002 or Spring 2003 semesters. Whereas such a small number of Muslim (n = 5), Hindu (n = 2), Buddhist (n = 1), and Jewish (n = 0) persons elected to participate, similar to Slade (1981), we restricted our sample to participants who indicated their religious affiliation to be Protestant (n = 93, 61.2 percent), Catholic (n = 25, 16.4 percent), or Other (n = 34, 22.4 percent). The final sample (128 women; 24 men) on which the remaining analyses were based was fairly diverse ethnically: 67 percent European American, 12 percent African American, 10.5 percent Hispanic, 6.5 percent Asian Pacific Islander, 1 percent American Indian, and 3 percent selected other as their ethnicity. We did not ask participants to indicate their specific belief in God (or Allah, etc.); however, we did ask participants two more general questions: To what extent do you consider yourself to be a religious person? and To what extent do you consider yourself to be a spiritual person? A majority of participants reported being religious (33.5 percent very religious, 41 percent moderately religious, 20.5 percent slightly religious, 5 percent not religious) and a majority indicated that they were spiritual (45 percent very spiritual, 39 percent moderately spiritual, 13 percent slightly spiritual, 3 percent not spiritual). Procedure The Christian-Muslim Implicit Association Test A Microsoft Windows-based software program (FIAT 2.3; Farnham 1998) was used to measure implicit Christian-Muslim attitudes (see also Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz 1998; Rudman et al. 1999). To complete this IAT, each participant sat at a computer terminal and read instructions on the monitor. Participants were instructed to press the a key (on the left of a standard keyboard) if the name or adjective that appeared on the screen fit into the category on the left of the screen and the 5 key (on the right number pad) if the name or adjective fit into the category shown on the right of the screen. After reading the instructions, each participant practiced categorizing the names and adjectives that appeared in a white rectangle in the middle of a light gray box on the screen. The following stimulus names and words were used. Judeo-Christian names: Jehovah, Yahweh, Elohim, Savior, Christ, Jesus, El Shaddai, Messiah, Immanuel, Adonai. Muslim names: Allah, Rahmaan, Quddoos, Salaam, Mumin, Muhaimin, Aziz, Jabbaar, Mutakabbir, Khaaliq. Pleasant words: pleasure, love, smart, joy, happy, wonderful, laughter, peace, luck, honor, gift, healthy, miracle, kind, hope, cheerful, fortune, moral. Unpleasant words: horrible,

6 34 JOURNAL FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGION awful, failure, nasty, agony, evil, war, terrible, poison, grief, disaster, hatred, evil, bomb, filth, accident, sorrow, misery. We decided to use Muslim and Christian names that appear in the Koran and the Bible instead of pictures of Muslim and Christian faces to avoid ethnicity confounds (e.g., pictures of Arab Muslims would confound ethnicity and religion) and because religious affiliation is not usually discernible from facial features. A total of seven blocks of trials were conducted with each participant. Blocks 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 were practice blocks with 20 trials per block. Reaction times were not recorded during practice blocks. Two data-collection blocks, with 40 trials per block, were conducted with each participant (Blocks 4 and 7). In the critical trials of this computerized test, reaction times were recorded as participants sorted words representing the four concepts (Christian, Muslim, unpleasant, and pleasant) into just two response categories (e.g., Incongruent condition: Muslim+pleasant; Christian+unpleasant; Congruent condition: Christian+pleasant, Muslim+unpleasant). For each trial in the test blocks, latency was recorded until the participant made a correct response. During practice and data-collection blocks, items from each category pair were selected randomly and without replacement so that all items were used only once before any items were reused. Each stimulus item was displayed until a correct response was made. The next stimulus item followed after a 150-ms intertrial interval. During data-collection blocks, the computer recorded elapsed time between the presentation of each stimulus word and occurrence of the correct keyboard response. As mentioned, IAT data for analyses were obtained from data-collection Blocks 4 and 7 (i.e., the congruent and incongruent conditions). Consistent with data-reduction and data-cleaning procedures described by Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz (1998), (a) the first two trials of each data-collection block were dropped because of their typically lengthened latencies, (b) data from participants with greater than 25 percent error rates for trials 4 and 7 were omitted before initial analyses were conducted (n = 8), (c) latencies less than 300 ms were recoded to 300 ms and latencies greater than 3,000 ms were recoded to 3,000 ms, and (d) a logarithm transformation was used to normalize the distribution of latencies. The Christian-Muslim IAT effect was computed by subtracting the mean log-latency to categorize terms in the congruent condition from the mean log-latency to categorize terms in the incongruent condition. A positive sample mean for the Christian-Muslim IAT effect (i.e., arithmetic mean > 0) would be evidence of implicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims or implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians. Measures of Social-Personality Dimensions Each participant also completed the following self-report measures. Participants total scores on each scale were divided by the number of items on the scale to facilitate comparison with other samples. 1. The Religious Fundamentalism Scale (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992) measures the belief that there is one set of religious teachings that clearly contains the fundamental, basic, intrinsic, essential, inerrant truth about human and deity; that this essential truth is fundamentally opposed by forces of evil which must be vigorously fought; that this truth must be followed today according to the fundamental, unchangeable practices of the past; and that those who believe and follow these teachings have a special relationship with the deity. (Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992:118) Each participant was instructed to indicate degree of agreement with each item (1 = very strongly disagree; 9 = very strongly agree; e.g., There is no body of teachings, or set of scriptures, which is completely without error ). 2. The Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale (see Altemeyer and Hunsberger 1992) taps selfreported authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, and conventionalism (1 = very

7 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS 35 strongly disagree; 9 = very strongly agree; e.g., Our country will be destroyed someday if we do not smash the perversions eating away at our moral fibers and traditional beliefs ). 3. The Christian Orthodoxy Scale Short Form (Hunsberger 1989) includes six items that assess the degree to which a person accepts Christian beliefs (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree; e.g., Jesus Christ was the divine Son of God ). 4. The Attitudes Toward Christianity Scale (Francis and Stubbs 1987) includes 24 items that assess perceptions of Christian behaviors (e.g., I want to love Jesus ; 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). We selected this scale because it was the most parallel existing measure to the IAT we could find (e.g., both measures include items about Jesus). Higher scores on this measure will be interpreted as more positive attitude toward Christians as a religious group. 5. The Attitudes Toward Muslims Scale (Altareb 1997) contains 25 items that tap five principal components (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree): Positive Feelings about Muslims (e.g., Muslims are friendly people ), Muslims as Separate or Other (e.g., I would support a measure deporting Muslims from America (reverse-keyed)), Restriction of Personal Choice/Freedom (e.g., Muslims are strict (reverse-keyed)), Fear of Muslims (e.g., Muslims should be feared (reverse-keyed)), Dissimilarity of Muslims (e.g., The Muslim religion is too strange for me to understand (reverse-keyed)). Higher scores on this measure will be interpreted as more positive attitude toward Muslims as a religious group. 6. The Anti-Arab Racism Scale (Pratto et al. 1994) contains five items about which people rate degree of positive or negative feeling (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive; e.g., Most of the terrorists in the world today are Arabs ). 7. The Social Dominance Orientation Scale (Pratto et al. 1994) contains 16 items that tap the degree to which a person desires that his or her in-group dominate and be superior to outgroups. Participants rate their feeling toward each item using a seven-point scale (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive; e.g., In getting what you want, it is sometimes necessary to use force against other groups ). 8. Measures of Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Quest religious orientations (Allport and Ross 1967; Batson, Schoenrade, and Ventis 1993) were administered to assess religious thoughts and behaviors as purposeful ends (intrinsic; 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), religious activities as a means to other personal or social ends (extrinsic; 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), and religious doubting, openness to religious change, and existential questioning (quest; 1 = very strongly disagree; 9 = very strongly agree). We elected not to report analyses with the social or personal components of extrinsic religious orientation because those variables internal consistencies were well below accepted standards (i.e., αs < 0.70). 9. The Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (Paulhus and Reid 1991) measures impression management with 20 items (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree; e.g., I have some pretty awful habits (reverse-keyed)) and self-deceptive enhancement with 20 items (e.g., I am a completely rational person ). Using the conventional scoring method, after reverse-keying appropriate items, participants received one point for each rating 6 and zero points for each rating 5. After completing the self-report scales, participants answered some demographic questions, returned their surveys, and were given credit for participation. On the whole, each self-report personality and attitude measure was internally consistent (see Table 1). RESULTS Baseline Levels of Explicit and Implicit Attitudes Toward Christians and Muslims Participants self-reported attitudes toward Christians (M = 5.20 when converted to a 6-point scale) were more positive than their self-reported attitudes toward Muslims (M = 4.20 on a

8 36 JOURNAL FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGION TABLE 1 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR MEASURES OF RELIGIOUS DIMENSIONS, PERSONALITY, AND ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS Personality and Attitude Measures Mean SD α Intrinsic Religious Orientation Extrinsic Religious Orientation Extrinsic-Social Extrinsic-Personal Quest Religious Orientation Christian Orthodoxy Religious Fundamentalism Right-Wing Authoritarianism Social Dominance Orientation BIDR Impression Management BIDR Self-Deceptive Enhancement Anti-Arab Racism Explicit Attitudes Toward Christians Explicit Attitudes Toward Muslims Christian-Muslim IAT Effect Relative Explicit Christian-Muslim Attitude IAT Conditions Congruent Latency (ms) Incongruent Latency (ms) Congruent Log-Latency Incongruent Log-Latency Note: Each measure was scored so that higher values represent higher levels of the personality or attitude dimension. The positive value of the Christian-Muslim IAT effect can be interpreted as implicit prejudice toward Muslim (relative to Christian). The variable Relative Explicit Christian-Muslim Attitude was created by subtracting each participant s self-reported attitude toward Christians z-scores from his/her self-reported attitude toward Muslims z-scores. 6-point scale), t(147) = 9.33, p < The same pattern was found at the implicit attitude level. Participants took significantly more time to categorize terms in the incongruent Christian-Muslim IAT condition than in the congruent Christian-Muslim IAT condition (Figure 1), what we call the Christian-Muslim IAT effect. In the incongruent IAT condition, the average log-latency was higher (M = 6.98, SD = 0.19) than in the congruent IAT condition (M = 6.69, SD = 0.17), t(69) = 17.96, p < In other words, participants took significantly longer to associate Muslim names with pleasant terms than to associate Christian names with pleasant terms and they took less time to associate the Muslim names with unpleasant terms than to associate the Christian names with unpleasant terms. This pattern was interpreted to be evidence of implicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims and implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians. Because women are typically more religiously committed than men (Stark 2002), we examined whether gender differences existed on the measures of these attitudes toward religious groups. Although women reported more positive attitudes toward Christianity (M = 6.38, SD = 0.77) than men (M = 5.72, SD = 1.27), F(1, 100) = 7.93, p < 0.01, no gender differences were found on self-reported attitudes toward Muslims (Women: M = 4.24, SD = 0.64; Men: M = 4.22, SD = 0.70) or on the Christian-Muslim IAT effect (Women: M = 0.30, SD = 0.13; Men: M = 0.28, SD = 0.15), Fs < 1, ns.

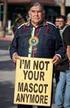

9 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS 37 FIGURE 1 MEAN LATENCY RESULTS FOR THE CHRISTIAN-MUSLIM IAT LATENCY (in ms) Incongruent Congruent IMPLICIT ASSOCIATION TEST (IAT) CONDITION Associations Between Measures of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Like other researchers who study the correspondence between implicit and explicit attitudes (e.g., Nosek 2004; Rudman et al. 1999), we maximized the comparability of the implicit and explicit measures by creating a relative explicit attitude variable to parallel the relative implicit measure. This variable was created by computing the difference between self-reported attitudes toward Christians and self-reported attitudes toward Muslims after each variable was standardized. A positive difference score can be interpreted as more favorable self-reported attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims and more negative self-reported attitudes toward Muslims relative to Christians. As shown in Table 2, implicit and explicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims correlated very slightly (r = 0.11). Similarly, Martin, Grande, and Crabb (2004) did not find a significant association between implicit and explicit measures of prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians. In comparison, Rudman et al. (1999) found reaction times to complete a very similar Christian-Jewish IAT correlated negligibly with self-reported pro-semitic attitudes (r = 0.12, ns). The pattern of small correlations suggests a possible disconnect or dissociation between the implicit activation of Christian-Muslim attitudes and the explicit expression of those attitudes by self-report. See Dovidio, Kawakami, and Beach (2001:182) for a more thorough discussion of the statistical relationship between explicit and implicit attitudes. Another analytic strategy we considered (but rejected) was to attempt to create an independent measure of implicit attitudes toward Muslims by subtracting the average reaction time in the pleasant/muslim condition from average reaction time in the unpleasant/muslim condition. After attempting to create such an independent IAT measure of association strength, Nosek, Greenwald, and Banaji (2004:17) concluded, the IAT cannot be analytically decomposed into separate assessments of association strengths. As such, like the hundreds of IAT studies conducted to date, the implicit measure in the current study is relative (i.e., implicit attitude toward Muslims relative to Christians), not independent. Researchers desiring to gain more control over the relative versus independent assessment of implicit attitudes could consider using the Go/No-Go Association Test (GNAT; Nosek and Banaji 2001). Personality Correlates of Attitudes Toward Christians and Muslims Bivariate Correlates of Self-Reported Attitudes Toward Christians As shown in Table 2, several religious dimensions correlated positively with self-reported attitudes toward Christians (i.e., religious fundamentalism, Christian orthodoxy, intrinsic religious

10 TABLE 2 ZERO-ORDER CORRELATIONS BETWEEN SOCIAL-PERSONALITY MEASURES AND ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS Religious Fundamentalism 2. Right-Wing Authoritarianism Christian Orthodoxy Attitudes Toward Christians Attitudes Toward Muslims Anti-Arab Racism Social Dominance Orientation Intrinsic Religious Orientation Extrinsic Religious Orientation Quest Religious Orientation BIDR Impression Management BIDR Self-Deceptive Enhancement Relative Explicit Christian-Muslim Christian-Muslim IAT Effect Gender (0 = Female; 1 = Male) Note: BIDR = Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding; IAT = Implicit Association Test; n = 152; r > 0.19, p < 0.05; r > 0.23, p < 0.01; r > 0.27, p < Scales were scored so that higher values indicated more of a particular dimension or more positive attitudes. Higher values on the relative explicit Christian-Muslim variable represent more positive attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims. 38 JOURNAL FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGION

11 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS 39 orientation). Extrinsic and quest religious orientations correlated negatively with attitudes toward Christians. Of the nonreligious personality constructs, self-reported attitude toward Christians was positively correlated with right-wing authoritarianism (r = 0.54, p < 0.001) and impression management (r = 0.20, p < 0.05). Partial correlations (controlling for impression management) were computed between variables shown in Table 2, but were not reported because the magnitude of associations described above did not change more than two or three one-hundredths of a point. Bivariate Correlates of Self-Reported Attitudes Toward Muslims Attitude toward Muslims correlated negatively with anti-arab racism (r = 0.78, p < 0.001), SDO (r = 0.40, p < 0.001), right-wing authoritarianism (r = 0.39, p < 0.001), and religious fundamentalism (r = 0.21, p < 0.05), indicating that as these dimensions of the self increase, explicit attitudes toward Muslims become more negative. Bivariate Correlates of Relative Explicit Christian-Muslim Attitudes Moderate to strong positive correlations were observed between the difference score (i.e., positive attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims) and religious fundamentalism, rightwing authoritarianism, Christian orthodoxy, anti-arab racism, and intrinsic religious orientation. Women reported more positive attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims than did men. Small negative correlations were observed between the difference score (i.e., positive attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims) and both quest and extrinsic religious orientations. Neither component of socially desirable responding (i.e., impression management and self-deceptive enhancement) correlated appreciably with this measure of attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims. Bivariate Correlates of the Christian-Muslim IAT Effect As shown in Table 2, the only apparent correlates of this implicit measure were self-reported attitudes toward Christians (r = 0.25, p < 0.01) and Christian orthodoxy (r = 0.19, p < 0.05). In other words, increases in positive attitude toward Christians and Christian orthodoxy are associated with more positive implicit attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims. It is also accurate to say that as self-reported attitudes toward Christians or Christian orthodoxy increase, implicit attitudes toward Muslims relative to Christians become more negative. DISCUSSION Christian-Muslim relations throughout history have varied widely from cooperative, peaceful dialogues and interactions to turbulent, combative encounters (Goddard 2000). Toward the ends of understanding and possibly improving Christian-Muslim relations, this study identifies some patterns and personality correlates of implicit and explicit attitudes toward Christians and Muslims within a predominantly Protestant sample in the United States. Overall, the patterns in this study are consistent with social identity theory (Tajfel 1982). That is, Christians implicit and explicit evaluations of the in-group (i.e., Christian) are more favorable than their implicit and explicit evaluations of the out-group (i.e., Muslim). Several personality dimensions correlate with self-reported evaluations of Christians relative to Muslims, but did not correlate as strongly with implicit evaluations of the religious groups. For example, self-reported anti-arab racism, social dominance, and right-wing authoritarianism correlate inversely with self-reported attitudes toward Muslims in this sample. Religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism, Christian orthodoxy, intrinsic religious orientation, and anti-arab racism correlate positively with self-reported preference for Christians relative to

12 40 JOURNAL FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGION Muslims. Only two variables, self-reported attitudes toward Christians and Christian orthodoxy, correlated positively with implicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims. It can also be interpreted that increases in self-reported attitudes toward Christians and Christian orthodoxy are associated with increases in implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians. The particularly strong association between self-reported anti-arab sentiment and selfreported attitudes toward Muslims merits discussion. As anti-arab racism increases, self-reported attitudes toward Muslims decrease sharply (r = 0.78). This finding could be a function of inaccurate cognitive stereotypes (e.g., thinking that most Muslims are Arabs when there are over 200 Muslim people groups around the world (Weekes 1984) or thinking that many Arabs are cunning, warlike, cruel, or unkind to women (see Slade 1981: Table 3)). The strong association between anti-arab racism and attitudes toward Muslims could also be due to pervasive in-group/out-group biases (i.e., thinking that one s in-group is better than out-groups; see Rowatt et al. 2002). Social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism both correlated negatively with self-reported attitudes toward Muslims (r = 0.40 and 0.39). Concerning social dominance, people in this predominantly Christian sample who desire their in-group to dominate and be superior to out-groups reported more negative attitudes toward Muslims (and more anti-arab racism). These patterns are consistent with previous findings that SDO correlates positively with anti-arab racism and attitudes toward the 1991 Iraq War (Pratto et al. 1994). The negative correlation between right-wing authoritarianism and self-reported attitude toward Muslims fits with an abundance of research showing right-wing authoritarians to be very ethnocentric and prejudiced (see Altemeyer 1996). We did not find self-report measures of right-wing ideology or religiosity to be particularly strong correlates of implicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims (or implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christian), and are not sure why. However, other recent research indicates that (a) self-report measures of right-wing ideology correlate with general implicit ethnocentrism (Cunningham, Nezlek, and Banaji 2004), (b) self-reported right-wing authoritarianism correlates with specific implicit prejudice toward blacks relative to whites (Rowatt and Franklin 2004), and (c) religious fundamentalism correlates with more specific implicit prejudice toward homosexuals relative to heterosexuals (Rowatt et al. 2004). The pattern of associations between quest and attitudes toward the two religions warrants brief discussion. Quest correlates negatively with both implicit (r = 0.14) and explicit measures of attitudes toward Christians relative to Muslims (r = 0.21). One could interpret this to be evidence of tolerance for Muslims relative to Christians (cf. Batson et al. 2001); however, in light of the other patterns between quest and self-report measures, it is more likely that quest associates with more negative attitudes toward Christians at the implicit and explicit levels. Many social-cognitive psychologists are particularly interested in the correspondence between implicit and explicit attitudes (e.g., Fazio and Olson 2003; Nosek 2004; Rudman 2004a). The magnitude of association we find, although small (r = 0.11), is very similar to the size of associations between implicit and explicit measures of prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians in another study (Martin, Grande, and Crabb 2004) and between implicit and explicit measures of prejudice toward Jewish persons relative to Christians (Rudman et al. 1999). This pattern of small correlations suggests a possible disconnect or dissociation between the implicit activation of interreligious attitudes and the explicit expression of those attitudes by self-report. The small correspondence between implicit and explicit attitudes could be due to a third variable (see Nosek 2004) or it could be the case that implicit and explicit attitudes originate from different sources (see Rudman 2004a). Before concluding, an alternative interpretation for the Christian-Muslim IAT effect and some sample characteristics merit brief discussion. First, we interpret the IAT effect in this study to be evidence of implicit preference for Christians relative to Muslims (or implicit prejudice toward Muslims relative to Christians). However, it could be argued that people in this sample more

13 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS 41 quickly sorted familiar names (of Christians) than less familiar names (of Muslims). Although this alternative interpretation is intuitively appealing, familiarity explanations for IAT effects have been carefully examined and ruled out by previous researchers (see Dasgupta et al. 2000; Greenwald and Nosek 2001; Ottaway, Hayden, and Oakes 2001) and were not directly tested in this study. Second, although this sample included more women than men, gender did not account for considerable variation in these attitudes. Third, even though a few Muslims participated (n = 5), we opted to focus our analyses on the responses of the larger subsample of non-muslims (n = 152). As such, the patterns in this study generalize best to non-muslims in the United States, specifically American Protestants and Catholics. Future research on predictors of ethnic prejudices among a larger sample of Muslims and with members of other minority groups could be conducted (cf. Rudman, Feinberg, and Fairchild 2002). In closing, we suggest that a better understanding of the social-personality correlates of attitudes toward Christians and Muslims might help partially account for the wide range of peaceful and turbulent Christian-Muslim relations throughout history (see Goddard 2000). This idea rests on the assumption that psychological attitudes correlate with actual related behaviors, and they do (see Bushman and Bonacci 2004; Kraus 1995). However, additional research on the correspondence between implicit attitudes and actual criterion behaviors is needed. Reducing explicit and implicit biases (see Rudman 2004b) and improving Christian-Muslim relations will likely be a significant challenge. With respect to personality, it is probable that individuals with less authoritarian and less socially dominant dispositions will express more positive attitudes toward the out-group, and possibly experience more constructive relations. Along the same line, cultivation of a more inclusive spirituality might increase positive attitudes toward Muslims by non-muslims, and might lead to more open, positive, and pleasant Christian-Muslim interactions. On the interpersonal level, broadening social identity might reduce pervasive ingroup/out-group biases. Expansion of one s social identity to be more inclusive could occur through personal reflection and dialogue within and between families, schools, businesses, religious and political organizations, and other community groups. Further contraction of social identity within existing in-groups will likely polarize groups and foster more negative attitudes and behaviors between groups. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Portions of this research were presented at the January 2004 meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (Austin, TX) and at the March 2004 meeting of the American Psychological Association s Division 36 (Psychology of Religion; Loyola College of Maryland). REFERENCES Allport, G. W. and J. M. Ross Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: Altareb, B. Y Attitudes towards Muslims: Initial scale development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Muncie, IN: Ball State University. Altemeyer, B The authoritarian specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Altemeyer, B. and B. Hunsberger Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: Asendorpf, J. B., R. Banse, and D. Mücke Double dissociation between implicit and explicit personality selfconcept: The case of shy behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: Banaji, M. R., K. M. Lemm, and S. J. Carpenter The social unconscious. In Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intraindividual processes, edited by A. Tesser and N. Schwarz, pp Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. Banse, R., J. Seise, and N. Zerbes Implicit attitudes towards homosexuality: Reliability, validity, and controllability of the IAT. Zietschrift fuer Experimentelle Psychologie 48: Batson, C. D., S. H. Eidelman, S. L. Higley, and S. A. Russell And who is thy neighbor? II: Quest religion as a source of universal compassion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40:39 50.

14 42 JOURNAL FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGION Batson, C. D., C. H. Flink, P. Schoenrade, J. Fultz, and V. Pych Religious orientation and overt versus covert racial prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50: Batson, C. D., S. J. Naifeh, and S. Pate Social desirability, religious orientation, and racial prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: Batson, C. D., P. Schoenrade, and W. L. Ventis Religion and the individual: A social-psychological perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. Bushman, B. J. and A. M. Bonacci You ve got mail: Using to examine the effect of prejudiced attitudes on discrimination against Arabs. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40: Crosby, F., S. Bromley, and L. Saxe Recent unobtrusive studies of black and white discrimination and prejudice: A literature review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87: Cunningham, W. A., J. B. Nezlek, and M. R. Banaji Implicit and explicit ethnocentrism: Revisiting the ideologies of prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30: Cunningham, W. A., K. J. Preacher, and M. R. Banaji Implicit attitude measures: Consistency, stability, and convergent validity. Psychological Science 12: Dasgupta, N., D. E. McGhee, A. G. Greenwald, and M. R. Banaji Automatic preference for white Americans: Eliminating the familiarity explanation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 36: Devine, P. G Implicit prejudice and stereotyping: How automatic are they?: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: Devos, T. and M. R. Banaji Implicit self and identity. In Handbook of self and identity, edited by M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney, pp New York: Guilford Press. Donahue, M. J Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48: Dovidio, J. F., K. Kawakami, and K. R. Beach Implicit and explicit attitudes: Examination between measures of intergroup bias. In Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intergroup processes, edited by R. Brown and S. Gaertner, pp Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. Duck, R. J. and B. Hunsberger Religious orientation and prejudice: The role of religious proscription, right-wing authoritarianism, and social desirability. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: Eagly, A. H. and S. Chaiken The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. Farnham, S. D FIAT 2.3 for windows [Computer Software]. Seattle, WA. Fazio, R. H. and M. A. Olson Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology 54: Francis, L. J. and M. T. Stubbs Measuring attitudes towards Christianity: From childhood to adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences 8: Franco, F. M. and A. Maass Intentional control over prejudice: When the choice of the measure matters. European Journal of Social Psychology 29: Gawronski, B What does the Implicit Association Test measure? A test of the convergent and discriminant validity of prejudice-related IATs. Experimental Psychology 49: Goddard, H Christian-Muslim relations: A look backwards and a look forwards. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 11: Goldfried, J. and M. Miner Quest religion and the problem of limited compassion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: Greenwald, A. G., M. R. Banaji, L. A. Rudman, S. D. Farnham, B. A. Nosek, and D. S. Mellott A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychological Review 109:3 25. Greenwald, A. G., D. E. McGhee, and J. L. K. Schwartz Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74: Greenwald, A. G. and B. A. Nosek Health of the Implicit Association Test at age 3. Zietschrift fuer Experimentelle Psychologie 48: Hassan, M. K Religious prejudice among college students: A socio-psychological investigation. Journal of Social and Economic Studies 3: Heaven, P. C. L. and D. St. Quintin Personality factors predict racial prejudice. Personality and Individual Differences 34: Herek, G. M Religious orientation and prejudice: A comparison of racial and sexual attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 13: Himmelfarb, S The measurement of attitudes. In The psychology of attitudes, edited by A. Eagly and S. Chaiken, pp Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Hogg, M. A Social identity. In Handbook of self and identity, edited by M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney, pp New York: Guildford Press. Hunsberger, B A short version of the Christian orthodoxy scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28: Religion and prejudice: The role of religious fundamentalism, quest, and right-wing authoritarianism. Journal of Social Issues 51:

15 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDES TOWARD CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS Religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism, and hostility toward homosexuals in non-christian religious groups. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 6: Hunsberger, B., V. Owusu, and R. Duck Religion and prejudice in Ghana and Canada: Religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism, and attitudes toward homosexuals and women. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: Kirkpatrick, L. A Fundamentalism, Christian orthodoxy, and intrinsic religious orientation as predictors of discriminatory attitudes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32: Kraus, S. J Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21: Laythe, B., D. G. Finkel, and L. A. Kirkpatrick Predicting prejudice from religious fundamentalism and right-wing authoritarianism. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40:1 10. Laythe, B., D. G. Finkel, R. G. Bringle, and L. A. Kirkpatrick Religious fundamentalism as a predictor of prejudice: Atwo-component model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: Madani, A. O Dissertation abstracts international: Section B The sciences and engineering. Depiction of Arabs and Muslims in the United States News Media 60(9-B):4965. Martin, M. R., A. H. Grande, and B. T. Crabb Watch the war, hate Muslims more? Media exposure predicts implicit prejudice. Poster presented at the 16th meeting of the American Psychological Society, Chicago, IL. McConnell, A. R. and J. M. Leibold Relations among the Implicit Association Test, discriminatory behavior, and explicit measures of racial prejudice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37: Nosek, B. A Moderators of the relationship between implicit and explicit attitudes. Unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia. Nosek, B. A. and M. R. Banaji The go/no-go association task. Social Cognition 19: Nosek, B.A., M. R. Banaji, and A. G. Greenwald Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration web site. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 6: Nosek, B. A., A. G. Greenwald, and M. R. Banaji Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Manuscript under editorial review. Ottaway, S. A., D. C. Hayden, and M. A. Oakes Implicit attitudes and racism: Effects of word familiarity and frequency in the Implicit Association Test. Social Cognition 19: Paulhus, D. and D. Reid Enhancement and denial in socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60: Pratto, F. and M. Shih Social dominance orientation and group context in implicit group prejudice. Psychological Science 11: Pratto, F., J. Sidanius, L. M. Stallworth, and B. F. Malle Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: Rowatt, W. C. and L. M. Franklin Christian orthodoxy, religious fundamentalism, and right-wing authoritarianism as predictors of implicit racial prejudice. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 14: Rowatt, W. C., A. Ottenbreit, K. P. Nesselroade Jr., and P. A. Cunningham On being holier-than-thou or humblerthan-thee: A social-psychological perspective on religiousness and humility. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: Rowatt, W. C., J. A. Tsang, J. Kelly, B. LaMartina, M. McCullers, and A. McKinley Associations between religious personality dimensions and implicit homosexual prejudice. Manuscript under editorial review. Rudman, L. A. 2004a. Sources of implicit attitudes. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13: b. Social justice in our minds, homes, and society: The nature, causes, and consequences of implicit bias. Social Justice Research 17: Rudman, L. A., J. Feinberg, and K. Fairchild Minority members implicit attitudes: Automatic ingroup bias as a function of group status. Social Cognition 20: Rudman, L. A., A. G. Greenwald, D. S. Mellott, and J. L. K. Schwartz Measuring the automatic components of prejudice: Flexibility and generality of the Implicit Association Test. Social Cognition 17: Slade, S The image of the Arab in America: Analysis of a poll on American attitudes. Middle East Journal 35: Stark, R Physiology and faith: Addressing the universal gender difference in religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: Tajfel, H Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology 33:1 39. Weekes, R. V Muslim peoples: A world ethnographic survey. Westport, CO: Greenwood Press. Wittenbrink, B., C. M. Judd, and B. Park Evidence for racial prejudice at the implicit level and its relationship with questionnaire measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72: Wylie, L. and J. Forest Religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism, and prejudice. Psychological Reports 71:

16

CHAPTER 4: PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION

CHAPTER 4: PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION CHAPTER OVERVIEW Chapter 4 introduces you to the related concepts of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination. The chapter begins with definitions of these three

CHAPTER 4: PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION CHAPTER OVERVIEW Chapter 4 introduces you to the related concepts of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination. The chapter begins with definitions of these three

RELIGIOSITY, THE SINNER, AND THE SIN: DIFFERENT PATTERNS OF PREJUDICE TOWARD HOMOSEXUALS AND HOMOSEXUALITY

RELIGIOSITY, THE SINNER, AND THE SIN: DIFFERENT PATTERNS OF PREJUDICE TOWARD HOMOSEXUALS AND HOMOSEXUALITY GIULIA LUISA BOSETTI ALBERTO VOCI LISA PAGOTTO UNIVERSITY OF PADOVA In this study, we analyzed

RELIGIOSITY, THE SINNER, AND THE SIN: DIFFERENT PATTERNS OF PREJUDICE TOWARD HOMOSEXUALS AND HOMOSEXUALITY GIULIA LUISA BOSETTI ALBERTO VOCI LISA PAGOTTO UNIVERSITY OF PADOVA In this study, we analyzed

Separating the Sinner from the Sin : Religious Orientation and Prejudiced Behavior Toward Sexual Orientation and Promiscuous Sex

Separating the Sinner from the Sin : Religious Orientation and Prejudiced Behavior Toward Sexual Orientation and Promiscuous Sex HEATHER K. MAK JO-ANN TSANG This study extends research on the relationship

Separating the Sinner from the Sin : Religious Orientation and Prejudiced Behavior Toward Sexual Orientation and Promiscuous Sex HEATHER K. MAK JO-ANN TSANG This study extends research on the relationship

Religious Orientation, Coping Strategies, and Mental Health. Lindsey Cattau. Gustavus Adolphus College

Religiosity & Stress 1 Running Head: RELIGIOSITY AND STRESS Religious Orientation, Coping Strategies, and Mental Health Lindsey Cattau Gustavus Adolphus College Religiosity & Stress 2 Abstract One hundred

Religiosity & Stress 1 Running Head: RELIGIOSITY AND STRESS Religious Orientation, Coping Strategies, and Mental Health Lindsey Cattau Gustavus Adolphus College Religiosity & Stress 2 Abstract One hundred

Relations among the Implicit Association Test, Discriminatory Behavior, and Explicit Measures of Racial Attitudes

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37, 435 442 (2001) doi:10.1006/jesp.2000.1470, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Relations among the Implicit Association Test, Discriminatory

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37, 435 442 (2001) doi:10.1006/jesp.2000.1470, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Relations among the Implicit Association Test, Discriminatory

How To Find Out If A Black Suspect Is A Good Or Bad Person

LAW PERUCHE ENFORCEMENT AND PLANTOFFICER RACE-BASED RESPONSES BASIC AND APPLIED SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY, 28(2), 193 199 Copyright 2006, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. The Correlates of Law Enforcement Officers

LAW PERUCHE ENFORCEMENT AND PLANTOFFICER RACE-BASED RESPONSES BASIC AND APPLIED SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY, 28(2), 193 199 Copyright 2006, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. The Correlates of Law Enforcement Officers

Chapter 13. Prejudice: Causes and Cures

Chapter 13 Prejudice: Causes and Cures Prejudice Prejudice is ubiquitous; it affects all of us -- majority group members as well as minority group members. Prejudice Prejudice is dangerous, fostering negative

Chapter 13 Prejudice: Causes and Cures Prejudice Prejudice is ubiquitous; it affects all of us -- majority group members as well as minority group members. Prejudice Prejudice is dangerous, fostering negative

Priming Christian Religious Concepts Increases Racial Prejudice

Priming Christian Religious Concepts Increases Racial Prejudice Social Psychological and Personality Science 1(2) 119-126 ª The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalspermissions.nav

Priming Christian Religious Concepts Increases Racial Prejudice Social Psychological and Personality Science 1(2) 119-126 ª The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalspermissions.nav

Religious fundamentalism and out-group hostility among Muslims and Christians in Western Europe

Religious fundamentalism and out-group hostility among Muslims and Christians in Western Europe Presentationat the20th International Conference of Europeanists Amsterdam, 25-27 June, 2013 Ruud Koopmans

Religious fundamentalism and out-group hostility among Muslims and Christians in Western Europe Presentationat the20th International Conference of Europeanists Amsterdam, 25-27 June, 2013 Ruud Koopmans

Religious Orientation and Prejudice: A Comparison of Racial and Sexual Attitudes

Religious Orientation and Prejudice: A Comparison of Racial and Sexual Attitudes Gregory M. Herek Yale University Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1987, 13(1), 34-44 Abstract Past research on

Religious Orientation and Prejudice: A Comparison of Racial and Sexual Attitudes Gregory M. Herek Yale University Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1987, 13(1), 34-44 Abstract Past research on

Harvesting Implicit Group Attitudes and Beliefs From a Demonstration Web Site

Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 1, 101 115 1089-2699/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2699.6.1.101 Harvesting Implicit

Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 1, 101 115 1089-2699/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2699.6.1.101 Harvesting Implicit

Course Descriptions Psychology

Course Descriptions Psychology PSYC 1520 (F/S) General Psychology. An introductory survey of the major areas of current psychology such as the scientific method, the biological bases for behavior, sensation

Course Descriptions Psychology PSYC 1520 (F/S) General Psychology. An introductory survey of the major areas of current psychology such as the scientific method, the biological bases for behavior, sensation

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE FAITH DEVELOPMENT, RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM, RIGHT-WING

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE FAITH DEVELOPMENT, RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM, RIGHT-WING AUTHORITARIANISM, SOCIAL DOMINANCE ORIENTATION, CHRISTIAN ORTHODOXY, AND PROSCRIBED PREJUDICE AS PREDICTORS

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE FAITH DEVELOPMENT, RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM, RIGHT-WING AUTHORITARIANISM, SOCIAL DOMINANCE ORIENTATION, CHRISTIAN ORTHODOXY, AND PROSCRIBED PREJUDICE AS PREDICTORS

SUBGROUP PREJUDICE BASED ON SKIN COLOR AMONG HISPANICS IN THE UNITED STATES AND LATIN AMERICA

UHLMANN Subgroup prejudice ET AL. based on skin color Social Cognition, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2002, pp. 198-225 SUBGROUP PREJUDICE BASED ON SKIN COLOR AMONG HISPANICS IN THE UNITED STATES AND LATIN AMERICA Eric

UHLMANN Subgroup prejudice ET AL. based on skin color Social Cognition, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2002, pp. 198-225 SUBGROUP PREJUDICE BASED ON SKIN COLOR AMONG HISPANICS IN THE UNITED STATES AND LATIN AMERICA Eric

Table of Contents. Executive Summary 1

Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Part I: What the Survey Found 4 Introduction: American Identity & Values 10 Year after September 11 th 4 Racial, Ethnic, & Religious Minorities in the U.S. 5 Strong

Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Part I: What the Survey Found 4 Introduction: American Identity & Values 10 Year after September 11 th 4 Racial, Ethnic, & Religious Minorities in the U.S. 5 Strong

Chapter 10 Social Psychology

Psychology Third Edition Chapter 10 Social Psychology Learning Objectives (1 of 3) 10.1 Explain the factors influencing people or groups to conform to the actions of others. 10.2 Define compliance and

Psychology Third Edition Chapter 10 Social Psychology Learning Objectives (1 of 3) 10.1 Explain the factors influencing people or groups to conform to the actions of others. 10.2 Define compliance and

Stereotypes Can you choose the real Native American?

Stereotypes Can you choose the real Native American? A. B. C. E. D. F. G. H. I. J. K. 1. Look at these pictures. Some of the people in the pictures are Native Americans and some are not. Which of the people

Stereotypes Can you choose the real Native American? A. B. C. E. D. F. G. H. I. J. K. 1. Look at these pictures. Some of the people in the pictures are Native Americans and some are not. Which of the people

OEP 312: INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY. Social psychology is a discipline with significant application to major areas of social life.

OEP 312: INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Course Description Social psychology is a discipline with significant application to major areas of social life. This study material is an introductory course

OEP 312: INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Course Description Social psychology is a discipline with significant application to major areas of social life. This study material is an introductory course

BLACK AMERICANS IMPLICIT RACIAL ASSOCIATIONS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERGROUP JUDGMENT

Ashburn Nardo, BLACKS IAT SCORES Knowles, AND and INTERGROUP Monteith JUDGMENT Social Cognition, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2003, pp. 61-87 BLACK AMERICANS IMPLICIT RACIAL ASSOCIATIONS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR

Ashburn Nardo, BLACKS IAT SCORES Knowles, AND and INTERGROUP Monteith JUDGMENT Social Cognition, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2003, pp. 61-87 BLACK AMERICANS IMPLICIT RACIAL ASSOCIATIONS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR

Reviewing Applicants. Research on Bias and Assumptions

Reviewing Applicants Research on Bias and Assumptions Weall like to think that we are objective scholars who judge people solely on their credentials and achievements, but copious research shows that every

Reviewing Applicants Research on Bias and Assumptions Weall like to think that we are objective scholars who judge people solely on their credentials and achievements, but copious research shows that every

SELF-CATEGORIZATION THEORY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ENGLISH CHILDREN. Martyn Barrett, Hannah Wilson and Evanthia Lyons

1 SELF-CATEGORIZATION THEORY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ENGLISH CHILDREN Martyn Barrett, Hannah Wilson and Evanthia Lyons Department of Psychology, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey

1 SELF-CATEGORIZATION THEORY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ENGLISH CHILDREN Martyn Barrett, Hannah Wilson and Evanthia Lyons Department of Psychology, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey

Prejudice and Perception: The Role of Automatic and Controlled Processes in Misperceiving a Weapon

ATTITUDES AND SOCIAL COGNITION Prejudice and Perception: The Role of Automatic and Controlled Processes in Misperceiving a Weapon B. Keith Payne Washington University Two experiments used a priming paradigm

ATTITUDES AND SOCIAL COGNITION Prejudice and Perception: The Role of Automatic and Controlled Processes in Misperceiving a Weapon B. Keith Payne Washington University Two experiments used a priming paradigm

Religious education. Programme of study (non-statutory) for key stage 3. (This is an extract from The National Curriculum 2007)

Religious education Programme of study (non-statutory) for key stage 3 and attainment targets (This is an extract from The National Curriculum 2007) Crown copyright 2007 Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

Religious education Programme of study (non-statutory) for key stage 3 and attainment targets (This is an extract from The National Curriculum 2007) Crown copyright 2007 Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

Journal of Experimental Child Psychology

Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 109 (2011) 187 200 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Child Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jecp Measuring implicit

Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 109 (2011) 187 200 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Child Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jecp Measuring implicit

Study Plan in Psychology Education

Study Plan in Psychology Education CONTENTS 1) Presentation 5) Mandatory Subjects 2) Requirements 6) Objectives 3) Study Plan / Duration 7) Suggested Courses 4) Academics Credit Table 1) Presentation offers

Study Plan in Psychology Education CONTENTS 1) Presentation 5) Mandatory Subjects 2) Requirements 6) Objectives 3) Study Plan / Duration 7) Suggested Courses 4) Academics Credit Table 1) Presentation offers

What s the difference?

SOCIAL JUSTICE 101 What s the difference? Diversity & Multiculturalism Tolerance Acceptance Celebration Awareness Social justice Privilege Oppression Inequity Action Oriented What is social justice? "The

SOCIAL JUSTICE 101 What s the difference? Diversity & Multiculturalism Tolerance Acceptance Celebration Awareness Social justice Privilege Oppression Inequity Action Oriented What is social justice? "The

Religious education. Programme of study (non-statutory) for key stage 4. (This is an extract from The National Curriculum 2007)

Religious education Programme of study (non-statutory) for key stage 4 and years 12 and 13 (This is an extract from The National Curriculum 2007) Crown copyright 2007 Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

Religious education Programme of study (non-statutory) for key stage 4 and years 12 and 13 (This is an extract from The National Curriculum 2007) Crown copyright 2007 Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

BAYLOR U N I V E R S I T Y

BAYLOR U N I V E R S I T Y IRT Series Vol. 10-11, No. 42 September 13, 2010 Profile of First-Time Freshmen from s, This report focuses on first-time freshmen from who reported their high school as a home

BAYLOR U N I V E R S I T Y IRT Series Vol. 10-11, No. 42 September 13, 2010 Profile of First-Time Freshmen from s, This report focuses on first-time freshmen from who reported their high school as a home

Psychology of Discrimination Fall 2003

Psychology of Discrimination Fall 2003 Instructor: Alexandra F. Corning, PhD Course Number: PSY 410 Course Time: Mondays and Wednesdays 11:45-1 Office: 101 Haggar Hall Office Hours: By appointment Contact:

Psychology of Discrimination Fall 2003 Instructor: Alexandra F. Corning, PhD Course Number: PSY 410 Course Time: Mondays and Wednesdays 11:45-1 Office: 101 Haggar Hall Office Hours: By appointment Contact:

Theological Awareness Benchmark Study. Ligonier Ministries

Theological Awareness Benchmark Study Commissioned by Ligonier Ministries TheStateOfTheology.com 2 Research Objective To quantify among a national sample of Americans indicators of the theological understanding

Theological Awareness Benchmark Study Commissioned by Ligonier Ministries TheStateOfTheology.com 2 Research Objective To quantify among a national sample of Americans indicators of the theological understanding

APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION

APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION OFFICE of ADMISSIONS, McAFEE SCHOOL of THEOLOGY MERCER UNIVERSITY 3001 MERCER UNIVERSITY DRIVE ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30341-4115 OFFICE: (678) 547-6474 TOLL FREE: (888) 471-9922 THEOLOGYADMISSIONS@MERCER.EDU

APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION OFFICE of ADMISSIONS, McAFEE SCHOOL of THEOLOGY MERCER UNIVERSITY 3001 MERCER UNIVERSITY DRIVE ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30341-4115 OFFICE: (678) 547-6474 TOLL FREE: (888) 471-9922 THEOLOGYADMISSIONS@MERCER.EDU

The Prejudice Paradox: How Religious Motivations Explain the Complex Relationship between Religion and Prejudice

The Prejudice Paradox: How Religious Motivations Explain the Complex Relationship between Religion and Prejudice Jay Jennings Temple University Although we think of religion affecting political discussions

The Prejudice Paradox: How Religious Motivations Explain the Complex Relationship between Religion and Prejudice Jay Jennings Temple University Although we think of religion affecting political discussions

Proposal of chapter for European Review of Social Psychology. A Social Identity Theory of Attitudes

1 SENT EAGLY, MANSTEAD, PRISLIN Proposal of chapter for European Review of Social Psychology A Social Identity Theory of Attitudes Joanne R. Smith (University of Queensland, Australia) and Michael A. Hogg

1 SENT EAGLY, MANSTEAD, PRISLIN Proposal of chapter for European Review of Social Psychology A Social Identity Theory of Attitudes Joanne R. Smith (University of Queensland, Australia) and Michael A. Hogg

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY CANTON, NEW YORK COURSE OUTLINE PSYC 340 SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY CANTON, NEW YORK COURSE OUTLINE PSYC 340 SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Prepared By: Desireé LeBoeuf-Davis, PhD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND LIBERAL ARTS SOCIAL SCIENCES

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY CANTON, NEW YORK COURSE OUTLINE PSYC 340 SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Prepared By: Desireé LeBoeuf-Davis, PhD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND LIBERAL ARTS SOCIAL SCIENCES

Cross-Cultural Psychology Psy 420. Ethnocentrism. Stereotypes. P. 373-389 Intergroup Relations, Ethnocentrism, Prejudice and Stereotypes

Cross-Cultural Psychology Psy 420 P. 373-389 Intergroup Relations, Ethnocentrism, Prejudice and Stereotypes 1 Ethnocentrism Inevitable tendency to view the world through one's own cultural rules of behavior

Cross-Cultural Psychology Psy 420 P. 373-389 Intergroup Relations, Ethnocentrism, Prejudice and Stereotypes 1 Ethnocentrism Inevitable tendency to view the world through one's own cultural rules of behavior

MAINE K-12 & SCHOOL CHOICE SURVEY What Do Voters Say About K-12 Education?

MAINE K-12 & SCHOOL CHOICE SURVEY What Do Voters Say About K-12 Education? Interview Dates: January 30 to February 6, 2013 Sample Frame: Registered Voters Sample Sizes: MAINE = 604 Split Sample Sizes:

MAINE K-12 & SCHOOL CHOICE SURVEY What Do Voters Say About K-12 Education? Interview Dates: January 30 to February 6, 2013 Sample Frame: Registered Voters Sample Sizes: MAINE = 604 Split Sample Sizes:

College Students Impressions of Managers without a College Degree: The Impact of Parents Educational Attainment

College Students Impressions of Managers without a College Degree: The Impact of Parents Educational Attainment James O. Smith, Department of Management, College of Business, East Carolina University,

College Students Impressions of Managers without a College Degree: The Impact of Parents Educational Attainment James O. Smith, Department of Management, College of Business, East Carolina University,

Spirituality and Moral Development Among Students at a Christian College Krista M. Hernandez

Spirituality and Moral Development Among Students at a Christian College Krista M. Hernandez Abstract This descriptive comparative study describes the spirituality of college students at different levels

Spirituality and Moral Development Among Students at a Christian College Krista M. Hernandez Abstract This descriptive comparative study describes the spirituality of college students at different levels

How To Measure An Index Of Racial Discrimination

Journal of Personality and Soclal Psychology 1998, Vol. 74, No. 6, 1464-1480 Copyright the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0022-35 14/98/$3.00 Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition:

Journal of Personality and Soclal Psychology 1998, Vol. 74, No. 6, 1464-1480 Copyright the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0022-35 14/98/$3.00 Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition:

IMPLICIT PRIDE AND PREJUDICE: A HETEROSEXUAL PHENOMENON?

In: The Psychology of Modern Prejudice ISBN 978-1-60456-788-5 Editor:Melanie A. Morrison and Todd G. Morrison, pp. 2008 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 9 IMPLICIT PRIDE AND PREJUDICE: A HETEROSEXUAL

In: The Psychology of Modern Prejudice ISBN 978-1-60456-788-5 Editor:Melanie A. Morrison and Todd G. Morrison, pp. 2008 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 9 IMPLICIT PRIDE AND PREJUDICE: A HETEROSEXUAL

Psychology 596a Graduate Seminar In Social Psychology Topic: Attitudes And Persuasion

Psychology 596a Graduate Seminar In Social Psychology Topic: Attitudes And Persuasion Spring, 2010; Thurs 10:00a-12:30p, Psychology Building Rm 323 Instructor: Jeff Stone, Ph.D. Office: 436 Psychology

Psychology 596a Graduate Seminar In Social Psychology Topic: Attitudes And Persuasion Spring, 2010; Thurs 10:00a-12:30p, Psychology Building Rm 323 Instructor: Jeff Stone, Ph.D. Office: 436 Psychology

Research Advances of the MIRIPS-FI Project 2012-2014. Experience with Scales Used in the MIRIPS-FI Questionnaire

Research Advances of the MIRIPS-FI Project 2012-2014 Experience with Scales Used in the MIRIPS-FI Questionnaire Finnish MIRIPS Group Department of Social Research, University of Helsinki Funded by the

Research Advances of the MIRIPS-FI Project 2012-2014 Experience with Scales Used in the MIRIPS-FI Questionnaire Finnish MIRIPS Group Department of Social Research, University of Helsinki Funded by the

Key concepts: Authority: Right or power over others. It may be a person such as a priest, a set of laws, or the teachings from a sacred text.

Is it fair? Is equality possible? Why do people treat others differently? What do we want? What do we need? What should our attitude be towards wealth? How should we treat others? How does the media influence

Is it fair? Is equality possible? Why do people treat others differently? What do we want? What do we need? What should our attitude be towards wealth? How should we treat others? How does the media influence

Corey L. Cook Curriculum Vitae

1 Corey L. Cook Curriculum Vitae CONTACT INFORMATION: Department of Psychology 815 North Broadway Saratoga Springs, NY 12866 Office: (518) 580-8306 Fax: (518) 580-5319 E-mail: ccook@skidmore.edu PROFESSIONAL